Base64 Decode

Simply input your data and click the "Decode" button.

Convert a Base64 string from "YmFzZTY0IGRlY29kZQ==" to "base64 decode" effortlessly.

Copy to clipboard(output)

Overview - Decode Base 64

Introducing Base64 Decode and Encode

Meet Base64 Decode and Encode, a powerful yet simple online tool designed to efficiently encode and decode Base64 data. Whether you need to transform data into Base64 format or decode it back into a human-readable form, our tool makes the process seamless and hassle-free.

Why Use Base64 Decoding?

Base64 decoding is essential for retrieving binary data that has been encoded to ensure safe storage and transmission. This process maintains data integrity and allows accurate reconstruction. It is widely used in applications such as email communication via MIME, as well as in data formats like XML and JSON.

Key Features

Character Set Compatibility

Our platform defaults to the UTF-8 character set, ensuring precise data conversion. If your encoded data originates from a different character set, you can manually select the correct one before decoding. Since Base64 encoding does not inherently store character set information, choosing the appropriate format is crucial for accurate results. For file uploads, the default binary option prevents unnecessary conversions, ensuring proper handling of all non-text documents.

Newline Handling

Different operating systems use varying line break characters. Before decoding, our tool standardizes these breaks based on your chosen settings. While this feature is not critical for file decoding, it enhances accuracy when processing text-based data.

Decoding Options

+ Decode Each Line Separately: This option enables the decoding of multiple Base64-encoded lines individually. It is particularly useful when handling structured data with separate encoded segments (not compatible with the split-line reconstruction feature).

+ Reconstruct Split Lines: Base64-encoded data is often stored as continuous text. Activating this option ensures that multi-line encoded data is accurately reconstructed following MIME (RFC 2045) specifications, which dictate a 76-character line limit (not compatible with the separate line decoding feature).

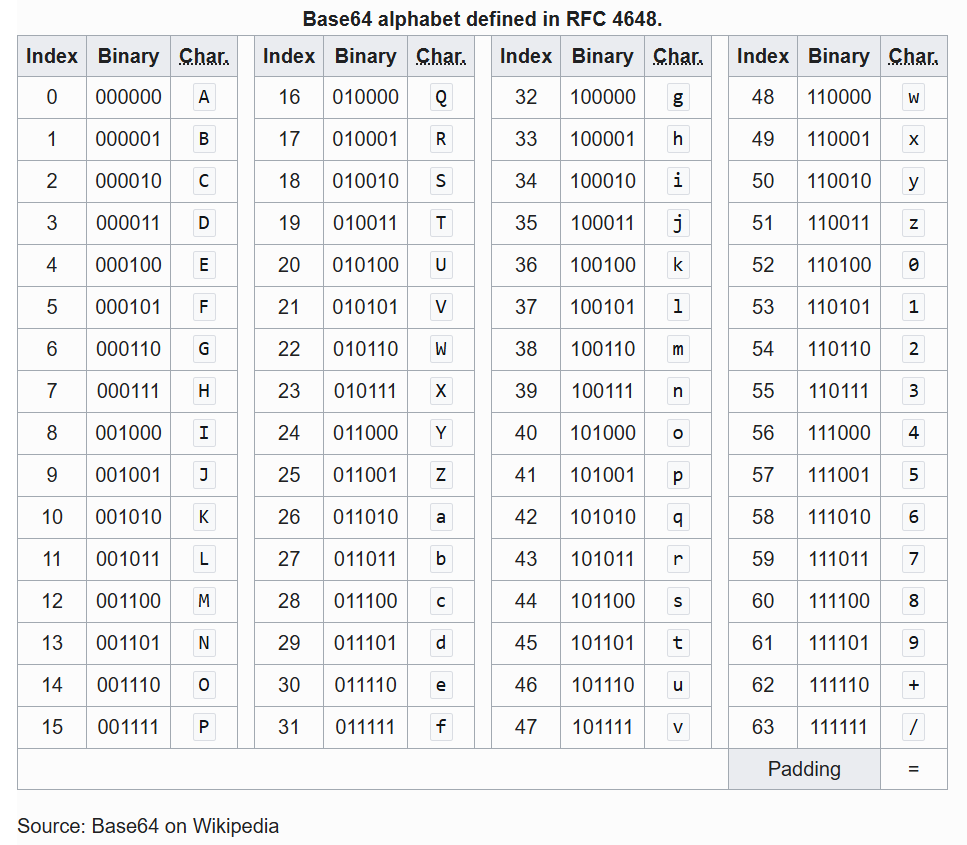

+ Handle URL-Safe Encoding: Some Base64 variations replace "+", "/", and "=" with URL-friendly characters like "-" and "_" to make them more suitable for web applications. Enabling this feature ensures proper decoding of such formats (RFC 4648 / Base64URL), restoring the original characters.

+ Live Mode: This setting enables real-time decoding using your browser’s built-in JavaScript functionality, ensuring immediate results without transmitting data to our servers. Currently, this mode supports only UTF-8 decoding.

Security and Privacy

Your data security is our priority. All communications with our servers are protected by SSL encryption (HTTPS). Uploaded files are automatically deleted after processing, and downloadable content is removed immediately after the first download attempt or after 15 minutes of inactivity—whichever occurs first. We do not store, inspect, or retain any submitted data or uploaded files. For further details, refer to our privacy policy.

100% Free to Use

Our Base64 decoding tool is completely free. No software installation is required—decode your data instantly online without hassle.

Understanding Base64 Decoding

Base64 decoding is the process of converting Base64-encoded data back into its original text or binary format. This technique is essential for reconstructing data that has been encoded for secure transmission and storage. Originally developed as a MIME content-transfer encoding, Base64 remains an integral part of modern digital applications.

Experience effortless, secure, and efficient Base64 decoding—try our tool today!

Base64 Decode - functions code

Home Page Base64Decode List Privacy Policy About Us Contact

This website uses cookies to enhance your experience, personalize content and ads, and analyze our traffic.

©2025 Design by base64decodeonl.com